“Unfortunately for corals the outlook is grim.” So says Nick Polato, a graduate student at Penn State University. “While some reefs will certainly endure, we are facing drastic declines both in the number and diversity of reefs as they deal with a host of man-made impacts, such as development and pollution, which aggravate effects of climate change.” Polato is a member of the team led by Iliana Baums, which last month had its research into the effect of temperature on young corals published in the journal PloS One. Polato points out that corals can’t move into more favourable environments except when they are in their young forms, known as larvae. “Our study showed high temperatures can really mess up the development of young corals,” he says, “so the ability of coral larvae to endure stress will be critical to the survival and recovery of affected reefs.”

Because corals don’t feature obviously in most people’s lives, it’s easy to underestimate their importance, Polato says. “Reefs matter because they protect shorelines from erosion, provide habitats for many species that we rely on for food, and that contain unique chemical compounds that we might be able to use to develop new drugs,” he explains. While he and his fellow researchers have looked at exactly how coral larvae respond to higher temperature, Polato emphasises that the loss of colour and death of mature coral has been well studied. “It is proven beyond reasonable doubt that corals bleach and eventually die in response to persistent warm water temperatures,” he says.

In fact Polato was initially surprised by how extremely sensitive corals are to rising sea surface temperatures (SSTs). “Studies have shown that even minor increases of only 2-3°C can cause corals to bleach and possibly starve,” he says. “Since even conservative estimates predict changes on this scale for much of the tropical ocean, major negative changes for reefs worldwide seem unavoidable.”

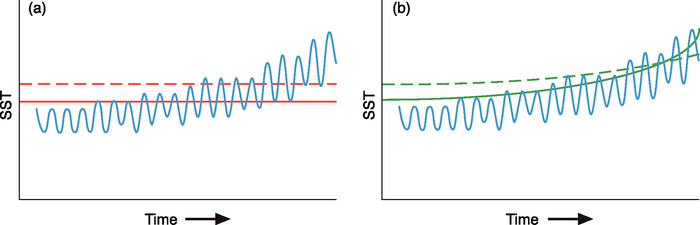

Alternative hypotheses concerning the threshold SST at which coral bleaching occurs; a) invariant threshold for coral bleaching (red line) which occurs when SST exceeds usual seasonal maximum threshold (by ~1°C) and mortality (dashed red line, threshold of 2°C), with local variation due to different species or water depth; b) elevated threshold for bleaching (green line) and mortality (dashed green line) where corals adapt or acclimatise to increased SST (based on Hughes et al., 2003). Credit: IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007

Climate change will also create problems for coral beyond those caused by temperature, Polato underlines. For example, rising sea levels will alter where corals can live, and some existing reefs will find themselves too deep to harvest the solar energy that they depend on for nutrition. “It is well documented that warmer oceans will lead to more frequent and intense storms that severely damage reefs and can require many decades to recover from,” Polato adds. “Also, a higher concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere makes surface waters more acidic, upsetting the delicately balanced chemical reactions that allow corals to grow.”

However, corals have lived on Earth for millions of years, seeing many climate changes in that time, and Polato believes that some will survive future warming. “But if we do nothing to conserve them, we may lose the cohesive ecosystems we know as coral reefs,” he warns. “Fortunately, as my research and others’ has shown, glimmers of hope do exist in the form of unexpected natural variation, and pockets of stress resistant individuals.”

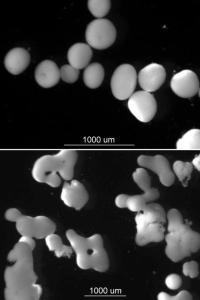

An increase of only 3°C results in severe developmental abnormalities in 2 day old Mountainous Star Coral embryos. In the sample collected from Florida, as much as 50% of all embryos observed at the higher temperature were malformed. Upper panel: normally developing coral embryos raised at 27°C, Lower panel: Malformed embryos raised at 30°C. Credit: Iliana Baums laboratory, Penn State.

In their PloS One paper the Penn State team found that coral larva from Florida were initially more sensitive to higher temperatures than Mexican larvae. “Gene expression – the production of whatever a gene holds the instructions for – can vary depending on environmental conditions,” Polato explains. “They can be turned up or down as needed – kind of like a thermostat. What’s interesting about our study is that these corals from Florida and Mexico are actually one large interbreeding population, not two separate populations. Based on the results of our experiment, we expect that the variation may be due to adaptation to local temperatures. This is surprising since both locations share the same gene pool, but if you look at the range of temperatures they have to deal with, where it is consistently warm in Mexico and varies seasonally from warm to cold in Florida, it makes a lot of sense.”

Now the researchers can use this data to begin breeding select individuals from these corals to improve temperature resistance. “We are not attempting to create any new species,” Polato emphasises. “We are trying to preserve and protect species that are already here.” They hope to spot how natural variation in coral populations influences their tolerance to high temperatures, acidity and disease, and their overall fitness. “Knowledge of this sort is important so we can conserve individuals that may be better at dealing with stress, and so we can forecast what will happen to reefs as the climate changes.”

July 22, 2010 at 4:25 am

“For example, rising sea levels will alter where corals can live, and some existing reefs will find themselves too deep to harvest the solar energy that they depend on for nutrition. ”

I think in the absence of other factors, rising sea levels are unlikely to exceed the rate of coral vertical accretion.

Check out http://www.springerlink.com/content/r72662715k01310r/

Cheers

Roger

http://www.rogerfromnewzealand.wordpress.com

July 24, 2010 at 4:06 pm

I pointed out your comment to Nick Polato and this is how he responded:

“In the absence of other factors I would be inclined to agree. Unfortunately that is not the case. The combination of changing coastlines, warming temperatures and increasing acidification are likely to reduce coral growth rates just as the rate of sea level rise is increasing. The growth rate of corals also depends on a number of things like what species it is, overall health, and where (how deep) it is growing.

This paper gives a good overview of potential outcomes:

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTCMM/Publications/21706633/HoeghGuldbergetal2007.pdf”

This is also touched on in this blog post: http://wp.me/pLahN-b6. Hope that clears things up for you.

Cheers,

Andy

December 22, 2010 at 11:36 am

[…] in this blog entry. The importance of this kind of warming is demonstrated by a diagram in this blog entry explaining why coral bleaches with higher temperatures. Other adverse effects of temperature […]