Lafayette College’s Kira Lawrence and her teammates have used ocean bed sediment cores, like this one, to produce a 5 million year climate record. © Intergrated Ocean Drilling Program

US, UK and Hong Kong Researchers have produce a unique ‘movie’ of climate reaching back 5 million years, by bringing together data drilled from ocean beds. It reveals three important temperature patterns during the warm early part of the Pliocene period that they couldn’t recreate together in climate models using existing explanations. That’s important because scientists hope the Pliocene could help us know what the future of a warmer Earth might be like. And having uncovered another layer to the Pliocene puzzle, team member Kira Lawrence from Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, underlined the value of finding its solution.

“Our community of scientists think of the Pliocene as though it was about 3°C warmer than modern temperatures with CO2 concentration about where we are right now,” Kira told me. “But we haven’t recognised before that the pattern of temperature was a lot different. If that’s where we’re headed in the not too distant future, if the temperature and precipitation patterns change in that way, we should have some significant things to think about.”

The Pliocene period started 5.3 million years ago, during which primates made important evolutionary steps towards humanity. Since 2000, there has been a climate data explosion reaching back through this era. Around the world, international drilling expeditions have pierced ocean beds kilometres below sea level, reaching hundreds of metres into sediment to bring back ‘core’ samples. Tiny fossils within that rock and mud can tell scientists temperatures through history, which can give climate scientists real data to test their models against.

Diverging from PRISM

An intenational ocean bed drilling programme has contributed to an “explosion” of temperature records reaching back to the Pliocene. © International Ocean Drilling Program

A project called PRISM has already done this using a 300,000 year temperature record starting 3,300,000 years ago, largely rebuilt from changes in the types of fossil in the sediment. When they used climate models to recreate the record’s temperature patterns, they found only very slight disagreements. Kira and her teammates have produced a much longer record mainly from the ratios between different types of fat and between the elements magnesium and calcium contained in the fossils. “The PRISM project looked at a snapshot of time,” Kira said. “But the reconstruction we’ve done is watching the movie from the Pliocene to the modern.”

Scientists already knew the Pliocene started warmly, with the northern part of the planet strangely ice-free, before it sank into the later icy Pleistocene epoch. Now, Kira’s team has found a surprisingly stable “warm pool”, where the tropical oceans stayed at around 29°C as the climate cooled elsewhere. By contrast, in the second important pattern they saw, sea temperatures nearer the North and South Poles were less stable. In the early Pliocene temperatures were closer in the poles and tropics, but steadily became more different. That difference increased as the Pliocene progressed, and also meant cold water could make its way to the tropics more often, affecting circulation there. That created “cold tongues” of water in the eastern Pacific and Atlantic, the third important pattern, which can still be seen today.

Previously five main ideas had been suggested to explain why the Pliocene was so much warmer and less icy than today, even though other conditions are similar. Kira’s teammates therefore wanted to see if climate models simulating those ideas would also recreate the patterns in their record, hoping that would mark one as correct. Chris Brierley from University College London in the UK and Alexey Federov from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut had both modelled the Pliocene climate many times before. They were surprised by the outcome of their efforts.

Theories fail the test

A huge pool of warm water that spanned the Tropics four million years ago is one of three features revealed in a 5 million year climate record. Models set up to simulate Pliocene climate according to five established theories failed to reproduces all these features at the same time. UCL's Chris Brierley explains the work and his concerns about its findings. Credit: Rob Eagle/UCL

Chris initially worked through each idea one-by-one. The first and perhaps most obvious possibility just raised CO2 levels. Two other solutions considered the fact that during the Pliocene, the continents were slowly moving to their current locations. During the Pliocene North and South America became linked by what is Panama today, closing a gateway between the Atlantic and Pacific. Chris modelled this and another, less dramatic, change that happened in Indonesia. And finally he tested two ideas related to how the climate works that models might not normally include properly. One is that the Pliocene experienced more hurricanes, which mixed the ocean more thoroughly. The other is that some clouds were less reflective, meaning that they would influence heat flow in the atmosphere differently.

None of the models containing these elements could produce the stable “warm pool”, early warmth nearer the poles, and “cold tongues” they saw in their records. “I was expecting going into this work that we would be able to say which of the five ideas we tested would be the one that came up with the right answer,” Chris told me. “Actually, none of them do.” However, the team did manage to get close by combining CO2, clouds and hurricanes.

In a research paper just published in Nature, the team underlined the importance of explaining why the models couldn’t recreate early Pliocene temperature patterns. Doing so is “essential for building confidence in our climate projections”, they write. Chris therefore is going on to look in more detail at the role of hurricanes, which are normally too small to include in climate models. That should help eliminate any unpleasant possibilities, he added. “Looking in the deep past is a way of uncovering nasty surprises that are normally low risk,” he said. “We don’t know why this ‘warm pool’ exists, so it could be flagging something nasty, but we also don’t know how likely that is.”

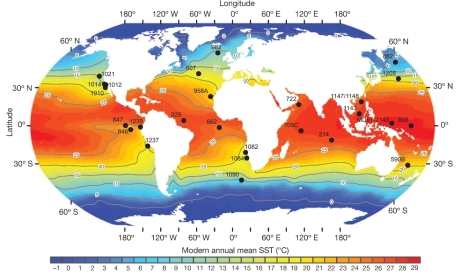

Map of the sites (black dots) that Kira, Chris and their teammates took data from, laid on a map of modern annual mean sea surface temperature. Numbers indicate particular sites from the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP), the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP), the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP), and the International Marine Past Global Study (IMAGES). Reproduced with permission from Nature, see below for citation.

Journal reference:

Fedorov, A., Brierley, C., Lawrence, K., Liu, Z., Dekens, P., & Ravelo, A. (2013). Patterns and mechanisms of early Pliocene warmth Nature, 496 (7443), 43-49 DOI: 10.1038/nature12003

Leave a comment