Global temperatures haven’t risen as much as the amount of energy the planet has absorbed since 2003 would suggest, but the rises may just have been delayed. That’s according to Kevin Trenberth and John Fasullo of the US National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

Kevin Trenberth explains where the sun’s energy goes when it reaches Earth. Credit: NCAR.

In a paper published in Science yesterday they compare satellite data measuring the amount of energy from the sun entering the atmosphere and returning back into space. Since 2000, the Earth has absorbed around 0.9 watts per square metre more at the top of the atmosphere than it has released. “It is this imbalance that produces global warming,” Trenberth and Fasullo write.

Most of the energy is absorbed by the oceans, with a comparatively small amount contributing to atmospheric warming. “Yet, ocean temperature measurements from 2004 to 2008 suggest a substantial slowing of the increase in global ocean heat content,” they write. “If the extra energy has not gone into the ocean, where has it gone?”

Most energy reaching the Earth from the sun is absorbed by the oceans – reflected by the blue area – with only part of the small portion up to the red line warming the atmosphere. Over recent years satellites have measured an increase in the amount of energy being retained on Earth, but it’s currently unclear where that energy has gone. Credit: Science.

In a separate statement the NCAR suggests that the heat may be stored in oceans so deeply that it’s currently impossible to monitor. Upper ocean waters across much of the tropical Pacific Ocean become significantly warmer around once every five years, in the cycle known as El Niño. The first signs of the latest El Niño emerged in June 2009, and Trenberth believes that this could now release the missing energy. “The heat will come back to haunt us sooner or later,” Trenberth. “The reprieve we’ve had from warming temperatures in the last few years will not continue.”

While directly measuring temperatures at great depths is not possible, Australian scientists presented evidence this week that surface warming has penetrated the oceans underneath. In the Journal of Climate, Paul Durack and Susan Wijffels analysed data on how the amounts of salt contained in the sea – known as salinity – changed across the world.

Understanding salinity is most important because it is one of the best measures of changes in rain and snowfall. “Observations of rainfall and evaporation over the oceans in the 20th century are very scarce,” Durack said. Salinity changes as oceans lose water to the atmosphere, making the sea saltier, and as it then returns to the sea as rain or snow it dilutes the salinity. “We can use ocean salinity changes as a rain-gauge,” Durack explains.

CSIRO scientist Dr Susan Wijffels holding an “Argo buoy” used to measure ocean salinity and temperature. Credit: CSIRO.

The Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Research Organization (CSIRO) scientists analysed measurements from 1950 to 2008, over which time surface sea temperatures have risen by 0.4ºC. They found that the oceans where most rain and snow falls have become fresher than ever, while those where more evaporation occurs have become still saltier. This implies that dry parts of the world have become drier and wet regions wetter as atmospheric temperature increases. “This is further confirmation from the global ocean that the Earth’s water cycle has accelerated,” Durack says. They also found that waters beneath the ocean’s surface have begun to move in the same direction as those at the surface. This is not usually expected. “Warming-driven changes are extending into the deep ocean,” Durack observed.

Kevin Trenberth was one of the scientists whose emails to Phil Jones of the University of East Anglia (UEA) were leaked as part of the “Climategate” scandal. This week UEA’s own independent scientific assessment panel, headed by former non-executive chairman of Shell Lord Oxburgh, became the latest to clear Jones’ science. The panel went through the the eleven papers written by Jones and the UEA’s Climatic Research Unit, including some relating to the controversial use of tree rings to measure temperatures through history. It assigned three members, at least one of which was familiar with the topic being written about, to each.

“We saw no evidence of any deliberate scientific malpractice in any of the work of the Climatic Research Unit,” the report concludes. “Rather we found a small group of dedicated if slightly disorganised researchers who were ill-prepared for being the focus of public attention.” However the panel was surprised that given the heavy use of statistics in the work that the CRU didn’t collaborate with any specialist statisticians. “There would be mutual benefit if there were closer collaboration and interaction between CRU and a much wider scientific group outside the relatively small international circle of temperature specialists,” it wrote.

Alongside Climategate, a cold winter in the UK and Europe has fuelled scepticism about global warming in affected countries over recent months. British and German scientists this week suggested that the comparatively low amount of energy currently coming from the sun may explain these cold temperatures. In a paper published in Environmental Research Letters on Wednesday, Mike Lockwood of the University of Reading and colleagues found a strong link between weak solar activity and the occurrences of a weather phenomenon known as “blocking”. This refers to weather systems that stay in the North Atlantic bringing cold north-easterly winds from the Arctic. As they do so, they “block” the jet stream which usually brings warmer weather from the west, over the Atlantic, and into Northern Europe.

“This year’s winter in the UK has been the 14th coldest in the last 160 years and yet the global average temperature for the same period has been the 5th highest,” Lockwood explains. “We have discovered that this kind of anomaly is significantly more common when solar activity is low.” As previously reported on Simple Climate, the sun produces higher or lower amounts of energy in approximately eleven year cycles. It is currently in the midst of a long “quiet spell”. Lockwood and his co-workers suggest that there is an approximately 8% chance that the Sun could in fact enter another extended quiet period, like the one known as the “Little Ice Age” – which lasted for 70 years – within the next 50 years. If the “quiet period” continues, they write, despite warming overall in the Northern hemisphere, “Europe could well experience more frequent cold winters than during recent decades”.

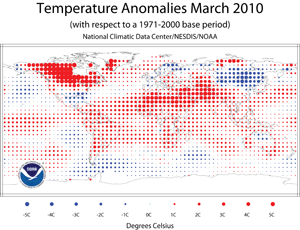

The global temperature differences from average for March. Red circles indicate higher temperatures, with larger red circles indicating a greater change. Credit: NOAA.

However, for those who would prefer to believe that the colder winters in their countries are an indication that global warming is an exaggeration there is one final piece of news this week that should give pause for thought. The US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration on Thursday said that March 2010 across the planet as a whole was the warmest on record. The combined global land and ocean average surface temperature was 13.5°C, 0.77°C above the 20th century average. The January-March period was the fourth warmest on record.

April 21, 2010 at 7:42 pm

[…] Saturday roundup: Hot water awaits? […]

May 26, 2010 at 5:22 pm

[…] Simple Climate reported in April, Durack and Wijffels used automated salinity measurements taken from devices called Argo […]

December 22, 2010 at 11:35 am

[…] in record temperatures in the US, average global annual temperatures for January-July, April, March, 2010 and 2009 overall. Plus I used the infamous “hockey-stick” graph showing how […]

May 5, 2012 at 2:57 pm

[…] who is currently at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California, Susan had previously used salinity to get round this. As oceans lose water to the atmosphere, the sea gets saltier, and as it then returns to the sea as […]

March 30, 2013 at 9:57 am

[…] 2010, Kevin went public over his worries about a budget that didn’t balance. But rather than money, that budget tallies heat energy from the Sun entering the top of the […]